A Q&A with Stephen Riegel, the author of “Finding Judge Crater,” a book that offers insight into a notorious unsolved mystery

“The book is the first to consider all the available evidence in the case and to offer a well-substantiated explanation of what happened to Joe Crater and why.“

— Stephen J. Riegel

SUP: Stephen, can you tell readers what your book is about in a few sentences?

Riegel: My book takes a new look at a famous old, unsolved missing person case – that of Judge Joseph Force Crater, who stepped into a taxicab in the middle of Manhattan on August 6, 1930, and was never seen or heard from again. Despite a massive manhunt across the country and the world that stretched over three decades, the New York Police Department and other investigators were unable to support or favor any of the numerous explanations of Crater’s disappearance, nor even answer more basic questions such as whether he vanished of his own accord or involuntarily at the hands of others. Making extensive use for the first time of new sources, including the NYPD files and court records, and taking a closer look at the missing man’s colorful life, time, and place – Manhattan at the end of the Jazz Age – the book is the first to consider all the available evidence in the case and to offer a well-substantiated explanation of what happened to Joe Crater and why.

SUP: What drew you to this subject?

Riegel: The subject of this book appealed to me for a number of reasons. First, having a background in the study of American History, the historical aspect of the story, which touches on Franklin D. Roosevelt and national politics, attracted me. I also became interested in the very different New York City of the Roaring Twenties – Tammany Hall, Mayor Jimmy Walker, its nightclubs, culture and corruption, all of which Crater figured in – that my book tries to portray. Also, as a lawyer practicing in the city, I better understood his successful legal and judicial career and its possible role in his disappearance, and the practice of law and the courts in the 1920s figure prominently in the story. Finally, the unsolved aspect of his disappearance presented a challenge and puzzle that I wanted to try to piece together.

SUP: Were there any other books on Judge Joseph Crater used as research, or is this book the first of its kind?

Riegel: This is the first comprehensive book-length treatment of Crater’s disappearance, so almost all of my research was done in primary sources. Only one other non-fiction account of his case previously has been published; recent attempts to solve the case have been in historical novels.

SUP: Can you describe the research process and difficulty?

Riegel: I did not find the research process for this book particularly difficult. Much of the research was done in libraries, archives and collections here in New York City. I was granted access to the NYPD files through a Freedom of Information Law request, and spent many hours in the basement of NYPD Headquarters, reviewing and taking notes of the contents of the remaining police files, but the people there who helped me were very cooperative throughout. My research also entailed extensive time reviewing the contemporary newspaper and magazine articles about the judge’s disappearance on a daily basis, which in conjunction with the NYPD files, gave me a real time sense of how the search progressed in the initial months of the investigation.

SUP: Would you say any part of Judge Crater’s disappearance has set a precedent for how similar cases are dealt with today?

Riegel: I don’t think so. The Crater case was unique, very much of its time and place.

SUP: What would you say will be the most fascinating aspect of this book for readers?

Riegel: Some readers of the book may be drawn mainly to its who-done-it aspect – its marshalling of the evidence in the case developed over thirty years, its analysis of the evidence against the different theories of Crater’s disappearance, and its presentation of a convincing explanation of how Crater disappeared and why. Others may find most interesting the book’s depiction of a rapidly transforming New York City at the end of the Roaring Twenties and the start of the Great Depression.

SUP: Who do you think will most enjoy this book? Who is the intended audience?

Riegel: I hope this book will appeal to a few audiences – those interested in famous historical mysteries, cold case/true crime investigations, New York City and State’ history, and lawyers and others curious about legal practice and history.

Stephen J. Riegel is a practicing litigator and former federal prosecutor in New York City who appears in some of the same courts Crater did. He also has degrees in American history from Princeton University and Stanford University. He has published articles on legal history.

October 12, 2021 | Categories: Author Spotlight, New Books | Leave a comment

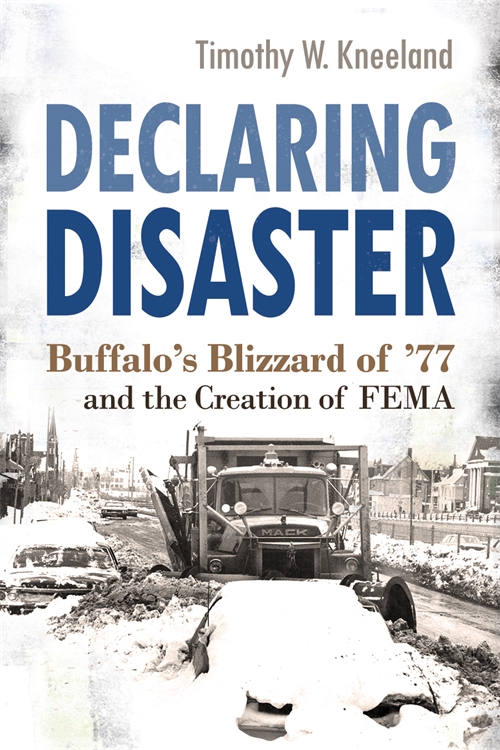

A Conversation With “Declaring Disaster” Author Timothy Kneeland

I realized that the significance of the blizzard was much greater than just a regional event and it was this story I wanted to tell.

SUP: In a nutshell how would you describe your upcoming book “Declaring Disaster”?

TK: This is the story of the Blizzard of ’77 and how it reshaped public policy, politics, and the identity of Buffalo New York. Although the ground blizzard made for challenging and life-threatening conditions, decades of public policies favoring private automobiles at the expense of public transportation; suburbs over cities, and the lack of coordinated emergency management made it a disaster.

SUP: What drew you to the subject?

TK: Like most of my work, there is a personal connection. I grew up in the Buffalo area and experienced the blizzard first-hand as a child. Most of the histories of this event focus on the drama-in-real-life elements. When I began work on the history of natural disasters and public policy, I realized that the significance of the blizzard was much greater than just a regional event and it was this story I wanted to tell.

SUP: Moved by the plight of the people of western New York, President Jimmy Carter issued the first disaster declaration on account of snow. What made this blizzard of ’77 so epic?

TK: The ferocity of the storm made it remarkable. Blizzard conditions lasted for five days and combined with severe cold and wind chills of as much as sixty below, compounded by snowdrifts which rose to thirty feet in some places, burying highways, cars, houses, etc. Transportation became nearly impossible, some utilities failed, and people were trapped in their homes, places of work, or in public buildings for days.

SUP: What lessons did the city of Buffalo learn from this disaster?

TK: Buffalo learned not to underestimate snow! It has been a watchword for years that mayors and other public officials show preparation before winter and respond with alacrity when a storm hits Buffalo. They created a local emergency management team that works with the state of New York and created a regional cooperative with the towns and villages in Erie County to share equipment and aid one another.

SUP: What areas of the book do you feel readers will find most fascinating?

TK: I think there is something for everyone! Readers will come to understand how the snowy environment of Buffalo shaped the city, find out the history of snow-fighting efforts in Buffalo through the 2014 storm that dropped as much as eight feet of snow in some areas of Buffalo, and take with them a cautionary tale of how private automobile ownership may have made us all a little less safe in wintertime!

SUP: There’s a chapter in the book called “Grab a Six Pack.” Can you tell readers what this chapter is about and its importance?

TK: Following the Blizzard of ’77, Buffalonians elected one of the more controversial mayors in city history, Jimmy Griffin, who took to heart the lesson of the previous mayor and made snow removal a priority. Unlike the previous mayor, who openly worried about large snowfalls, Griffin famously responded to a winter storm that fell on a weekend with the line that everything was fine, and residents should just “grab a six pack and watch a good ball game.” In fact, all mayors following the Blizzard of ’77 have shown good instincts in dealing with snow control on city streets.

SUP: How have the decisions made during the Blizzard of ’77 impacted how storms are handled today?

TK: Snowbelt cities have become smarter and employed more resources and greater technology to effectively respond to snow. Buffalo and most snowbelt cities are prepared for average or above-average storms and these lessons may need to be applied to those cities in the South which will experience snowstorms due to climate change.

SUP: Who do you feel will find this book invaluable?

TK: I think the general public will find much to think about from this book; I also imagine it might be useful for environmentalists, disaster policy experts, and for those interested in the history of the Buffalo.

Timothy W. Kneeland is professor and chair of history and political science at Nazareth College. He is the author of Pushbutton Psychiatry: A Cultural History of Electroshock in America and Playing Politics with Natural Disaster: Hurricane Agnes, the 1972 Election, and the Origins of FEMA.

His new book, Declaring Disaster: Buffalo’s Blizzard of ’77 and the Creation of FEMA, can be preordered at press.syr.edu.

author photo courtesy of Nazareth College of Rochester

February 8, 2021 | Categories: Author Spotlight | Leave a comment

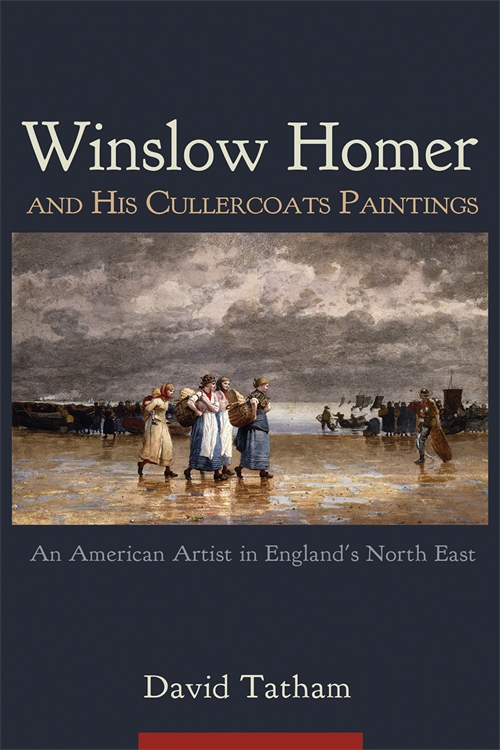

An Interview with David Tatham author of Winslow Homer and His Cullercoats Paintings

SUP: David, you’ve written extensively on Winslow Homer. What drew you to dedicate so much of your time exploring the life and work of this 19th century world-renowned American Artist?

DT: You are right in saying that a good deal of my published work concerns the artist Winslow Homer. This has been encouraged by the fact that the sites in which Homer sets his work: Boston, New York, The Adirondacks, Quebec, and London are places I know well, and in which I feel at home. This adds a further element of realism to what I see in his work.

SUP: This book happens to be about one of Winslow Homer’s most creative and productive times in his life, which many refer to as his “turning point.” What are the main aspects that you think influence this? What do you think made this time so influential for him?

DT: Yes, you are right on the mark when you say that the book is about one of Homer’s most creative and productive times. This was indeed a “turning point”, but it seems to me that the meanings typically given to that term in the Homer literature tend to be unhelpful. Some claim that homer’s subjects shifted wholesale to scenes of storms at seas and of fishermen coping with dangers, but scarcely any of these things have prominence or even simple appearances in his work. There was indeed a “turning” and it proved to be a major one. The change was not in Homer’s paintings so much as in his standing as an artist. The Cullercoats paintings and those that quickly followed established him as stronger, more powerful painter than his preceding paintings had suggested. After his final exhibition of Cullercoats paintings in New York and those that quickly followed, Homer was clearly a “major” American painter and then some. This was his “turning.”

SUP: Was there any specific work of art that stood out to you from Winslow Homer’s time in Cullercoats?

DT: Yes indeed. Top of the list is Beach Scene 1881. An amazing composition of four human figures, you don’t forget that dangling arm vividly set against a wrecked coble and then a misty background of other figures. In these respects, there is nothing else quite like it in Homer’s work. I wonder whether his No. 1 Cullercoats model, Maggie Jefferson, may have had a hand in organizing this work. She is the child minder in this scene.

SUP: It seems as if many different historians have their own take on Winslow Homer’s life. Are there any misconceptions about him that you would like readers to know?

DT: Many different historians have varied “takes” on Homer as a person, but all present him as a deeply serious artist much attached to his parents and other family members, and quite reserved even with his few friends. He was not a “hermit” as the press sometimes described him. He was certainly well respected as a person in Cullercoats.

SUP: This point in time is seen as a very influential time in Winslow Homer’s life. Mariana Van Rensselaer said in one of her reviews that his style shifted to having a “freedom from conventionality of thought” during this time. What aspects of this time do you think aided him in this?

DT: I am glad that you have cited Mariana Van Rensselaer’s essay on Homer, for though it considers him as still a relatively young man and developing artist, it remains a wonderfully insightful essay on both the artist and his works the years in and surrounding his time in Cullercoats. His new concept of the essence of the experiences of working women – an essence distinctly positive in every respect – is revelatory. He shows little of the hard laboring men–the fishermen–but makes it abundantly clear that these are not peasants nor are their wives. In this he broke from long standing traditions on the Continent and even elsewhere in England, to define and portray fisherfolk as of a lower social class.

SUP: Winslow Homer’s work during this time strayed away from focusing on the men of the community and placed an emphasis on nature and younger women in this area. What aspects of his life in Cullercoats do you assume made him more successful than other artists in the area who might have had a more holistic inspirational view of Cullercoats?

DT: Homer seems to have spent more time with the village women and older girls than did other artists in the community or beyond, and in this he is certain to have used his American mannerisms–social openness, good humor–generosity of spirit–and so forth. He transformed the manner in which he had painted American younger women a few years earlier.

SUP: Do you think your knowledge of art history has impacted your writing style? If so, how?

DT: I believe that my knowledge of art history, both from its literature and from my familiarity with various masterworks, has had relatively little impact on the writing style of evident in my books and articles about Homer.

SUP: Winslow Homer later decided to make renditions of his watercolor works into etched pieces. He took out certain aspects of pieces to make other parts stand out more, such as the handrail in etched version of Perils of The Sea. How do you think changing medium/technique impacted his work?

DT: I am sure that Homer turned to etching as a medium for revised versions of a few of his Cullercoats paintings for two reasons. First, his income. There was a fair chance that new and revised versions of certain of his Cullercoats paintings, now printed on paper, would add a welcome amount to his income. Second, a vogue for the medium of etching had arisen among American fine artists and it seemed likely that Homer saw a way to excel while remaining a fellow participant in the uses of the new medium.

November 16, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight | Leave a comment

This month scholars will participate in the 75th Annual Iroquois Research Conference. In celebration of this conference, Syracuse University Press is featuring an interview with Laurence M. Hauptman.

Laurence Hauptman is a SUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History who first attended and presented at the Iroquois Research Conference in 1974. Hauptman is the author of eight books published by Syracuse University Press including Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations Since 1800 that focuses on the lives and contributions of numerous women and men who shaped Haudenosaunee history.

SUP: Professor Hauptman– You have written numerous articles as well as 8 books on the Haudenosaunee/ Iroquois published by Syracuse University Press. Yet, you yourself are not a member of the Six Nations. What drew you to your lifetime commitment to write their history and what why did you approach the subject in the way you did?

LH: Fifty years ago, after reading Anthony F. C. Wallace’s The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca while in graduate school, I made it my point to familiarize myself with the literature on the Haudenosaunee, I noticed that most of the scholarship was written by anthropologists and that there was a gap in the historical literature after the death of Handsome Lake in 1815. Encouraged by a friends, anthropologist Jack Campisi, and historian William T. Hagan, I was determined to fill in that gap by writing 19th and 20th century Haudenosaunee history.

My career as a historian also grew out of a boyhood interest in the American Civil War. I was a junior in high school during the centennial of the Civil War in 1961. From this research, I learned an important lesson, namely that military historians visit the National Archives, but also go to visit and walk the ground of Civil War sites to gain a firsthand understanding of the topography of the battlefield. Combining archival research with on-site visits and interviews in Native communities grew out of this thinking. In the process of doing fieldwork, I was to meet some of the most amazing and heroic Haudenosaunee people from Hogansburg to Green Bay and learn valuable lessons, especially from Gordy McLester, my dear friend and co-author/ co-editor on five books,. who died from Covid-19 in May..

My graduate-school training at New York University led me first to American diplomatic history and then to coursework in anthropology. After reading the wonderful writings of historian Akira Iriye, I understood how important it is to look at competing sides in international relations and what he meant by a “culture and power” approach, namely how nations see their interests through the prism of their own cultures. Hence, I never saw doing Native American history as racial minority history with all the assumptions that that conveys, but rather in a global framework since they are transnational peoples with treaties. By studying international relations, I became more aware of the need for fieldwork to understand how people think, and that to do Iroquois history, you could not merely view things from what is in the archives in Washington. Albany, or Ottawa.

In early 1968, my mentor Bayrd Still, a fine teacher-scholar of urban America and the American West, gave me advice: “We historians here do not know about Indians.” To him, the only scholars interested in what was considered an esoteric subject at the time were anthropologists. Praising his friend, the well-known anthropologist E. Adamson Hoebel, he pointed across campus to the anthropology department. When I took my first anthropology course with the eminent anthropologist June Nash, she described her own work with the Maya in Guatemala and indicated to all five of us in her graduate seminar that contact with living people was acceptable and even encouraged by the discipline of anthropology. I had not heard that point made in any of my history classes before. A light bulb appeared in my head — the exciting thought of schmoozing with live human beings! [My father was a great “schmoozer” who could make conversation with anyone, especially about baseball; he apparently gave me this ”gift.”]

My first venture into “Indian history” was my masters-level essay on the (Dawes) General Allotment Act and post-Civil War reform, completed in 1968. In 1971, in one of the ironies of my life, I was hired at SUNY New Paltz, just 5 miles from where these reformers had met at Lake Mohonk to discuss the merits of the Dawes General Allotment Act from the early 1880s until 1929.

SUP: Which of the numerous women and men you treated in Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations since 1800 made the biggest impression on you and changed your thinking?

LH: Ernest Benedict (Mohawk). I had the privilege of knowing Chief Benedict for a quarter of a century thanks to his niece, my friend Kay Olan. He represented the very best in the Haudenosaunee world, a true intellectual and one totally committed to the ideals set forth in the Great Law of Peace. Sometimes historians are too cynical and miss the point that sheer idealism can be a motivating factor in human behavior. Chief Benedict cared deeply about his people and fought from the age of fifteen for Haudenosaunee border crossing rights set under the Jay Treaty of 1794. He viewed Native Peoples in an international context whose existence was being threatened by the ever-increasing pressures of “development” worldwide, leading him to found the influential Akwesasne Notes on his kitchen table in the late 1960s.

SUP: If you were able to magically go back in time and sit down with an Haudenosaunee leader from one of your books, which one would it be and why?

LH: Chief Daniel Bread (Oneida). I wrote about Chief Bread in a chapter in Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership published by Syracuse University Press and a in a full scale biography co-written by my dear friend, the late Gordy McLester, published by the University of Oklahoma University Press. I was fascinated by Bread’s skills as a politician. He managed to hold onto power from the 1820s to the 1870s. His skill led the Oneidas to plant permanent roots in Wisconsin. He carefully brought the influential Jackson Kemper, first Frontier Bishop of the Episcopal Church and later Bishop of Wisconsin, into the Oneida orbit, using Haudenosaunee metaphors reminiscent of the Condolence Council; Kemper responded by becoming the Oneidas’ protector in Wisconsin. Bread even debated Indian removal and the fate of his Oneidas with President Andrew Jackson at the White House in 1831.

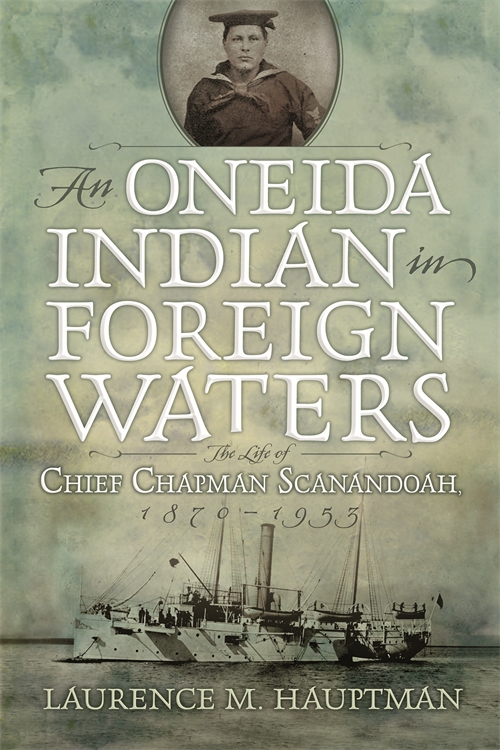

SUP: Your most recent book published with the Syracuse University Press was An Oneida Indian in Foreign Waters The Life of Chief Chapman Scanandoah, 1870-1953 (2017). Tell us about what makes Chief Chapman Scanandoah so important for you to write his biography?

LH: Chief Chapman Scanandoah. Chief Chapman Scanandoah was truly a remarkable individual. He was a well-trained mechanic, a decorated Navy veteran, a prize-winning agronomist, a historian, linguist, and philosopher, an early leader of the Oneida land claims movement, and a chief of the Oneidas. However, his fame today among his Oneida people rests with his career as an inventor. His whole life, he challenged stereotypes. On March 1, 1926, a reporter wrote about Scanandoah’s scientific accomplishments:“Chief Chapman Schanandoah [Scanandoah], sachem, Oneida Tribe of Iroquois and a resident of the Onondaga reservation at Nedrow, has won recognition from the Great White Father as an inventor in the realm of science which always has seemed the white man’s realm… He holds the confidence and the rapport of the dusky men and women in the midst of where he lives. They are glad he has won this honor in the world outside their valley and has proved the Indian of today knows tools, machines, and molecules.”[1] His life, 1870 to 1953, illustrates the Haudenosaunees’ remarkable ability to adapt to change, a major reason why all of the Six Nations in New York still maintain today a government-to-government relationship with the United States.

Scanandoah successfully managed to succeed in nearly everything he did. He was an outsider at the primarily African American Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia where he was educated in the late 1880s and early 1890s; one of the very few Native Americans in the United States Navy from 1897 to 1912 who traveled throughout the world; an Oneida with no land or political rights on the Onondaga Reservation where he resided for much of his life; a litigant in the white man’s court attempting to prevent the loss of the last remaining Oneida lands in the Empire State; a Native American inventor earning patents in the age of Thomas Edison; and one of the founders of the Indian Village at the New York State Fair.

SUP: If you were to write another book about the Haudenosaunee people in 2020, what would you focus on?

LH: I would write about the important roles attorneys play and have played in Haudenosaunee existence. Over the past half century, much of my historical research and consulting work has led me to examine historic litigation by numerous attorneys, thirty- three in all, hired to protect tribal lands and sovereignty. Although some were incompetent or unscrupulous, others I encountered in my research—e.g. James Clark Strong and George Palmer Decker – or personally worked for—e.g. George Shattuck, Arlinda Locklear (Lumbee), Jeanne Whiteing (Blackfeet)—were well versed in Haudenosaunee and American history. In order to develop strategies and represent their clients well, they like historians had to master the documents. I have found that too often historians equate the origins of every strategy affecting Native Americans in the courts entirely with chiefs, tribal chairman, and tribal councils. They all were/are very important, but many of the legal theories used in litigation were hatched by their attorneys.

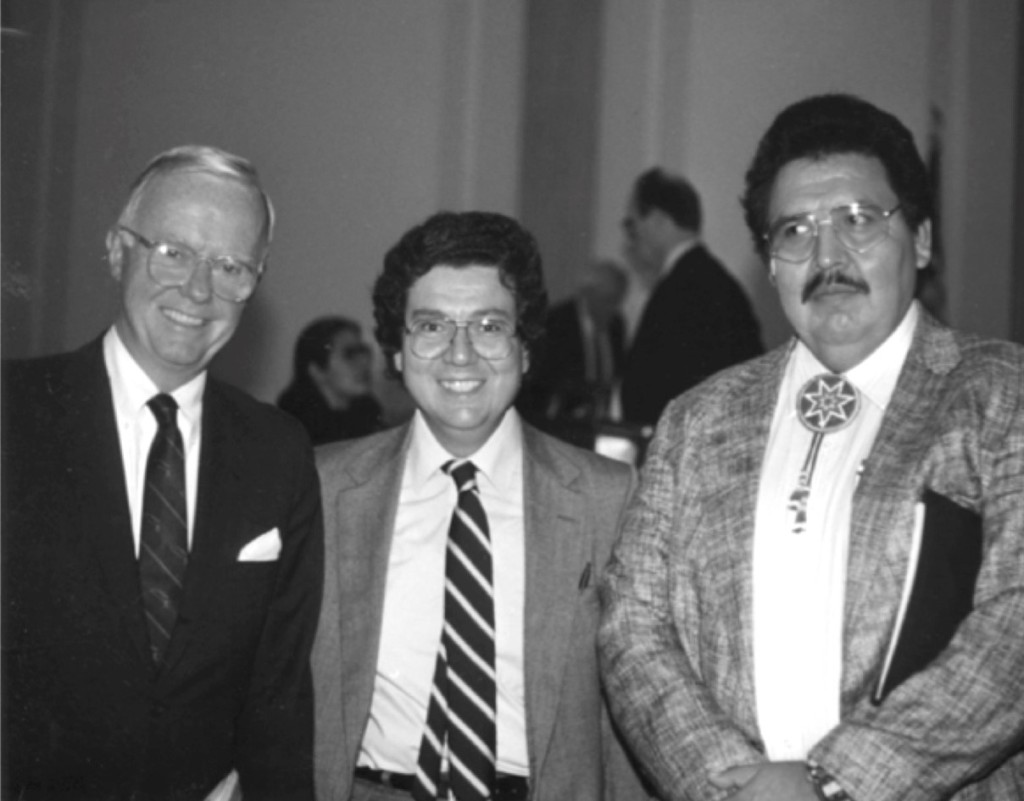

The House of Representatives’ Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs’ Subcommittee on Indian Affairs’ hearing on the Seneca Nation Settlement Bill, September 13, 1990. Shown left to right are three who testified on the Seneca Nation’s behalf: Congressman Amory Houghton, Jr., the sponsor of the legislation; Dr. Laurence M. Hauptman, who served as the historical expert witness on the leases; and Dennis Lay, President of the Seneca Nation of Indians.

October 14, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight | Leave a comment

INTERNATIONAL TRANSLATION DAY featured interview with Rachel Mines, translator of ‘The Rivals and Other Stories’

Today in honor of International Translation Day the Syracuse University Press would like to introduce you to ‘The Rivals and Other Stories’ translator Rachel Mines, a Yiddish Book Center Translation Fellow and recently retired teacher in the English Department at Langara College in Vancouver, Canada.

SUP: ‘The Rivals and Other Stories’ has been called “a hidden treasure of modern Yiddish literature” what can you tell us about the author Jonah Rosenfeld?

RM: Jonah Rosenfeld was a prolific and popular writer in his time, but because he wrote exclusively in Yiddish and was hardly ever translated, he has virtually vanished from the American literary canon. Rosenfeld deserves to be put back on the map because so many of his stories are relevant today – and not only for Jewish readers.

Rosenfeld was born in 1881 into a poor family in Chartorysk, Volhynia, in the Russian Empire. His first years were tragic. When he was 13 years old, his parents died and his brothers sent him to Odessa to learn a trade. He was apprenticed to a lathe operator. According to his autobiography, he was abused and his teenage years were miserable.

Perhaps seeking an outlet for his feelings, Rosenfeld began writing in his early 20s. He published his first story in 1904 and his first collection of short stories appeared five years later. In 1921, Rosenfeld emigrated to New York City, where he became a major literary contributor to the leading Yiddish newspaper, the Forverts. He was known as a psychological writer, an author who dove deep into his characters’ psyches to explore their subconscious feelings and urges.

SUP: This work has been called an original contribution to the art of Yiddish short fiction in English translation.What drew you to the field of translating Yiddish works?

RM: I was raised by Yiddish-speaking parents, but I wasn’t much interested in the language or literature until about 15 years ago, when I met my mother’s cousin, who had survived the Holocaust and was living in Latvia. I got inspired to return to Yiddish so I could speak with Bella in her own language. Eventually I decided I wanted to take my studies further. As a literature teacher, I came to realize that Yiddish literature in translation could be taught in the classroom – even to students like my own, who weren’t necessarily Jewish. So translating seemed like the next logical step.

I also wanted to contribute to scholarship in general. Yiddish literature (and other texts in Yiddish) are not accessible to the great majority of scholars and researchers. Therefore, we can’t even start to address topics such as the place of Jonah Rosenfeld – to take just one example – in the American literary canon. Many fields of Yiddish writing are still waiting to be explored, but the works need to be translated first.

SUP: The Yiddish Book Center has uncovered over a million books originally written in Yiddish. Can you tell our readers what drew you to Jonah Rosenfeld’s short fiction?

RM: Some years ago, I was looking online for short stories I could read to practice my Yiddish. I found two of Jonah Rosenfeld’s stories on the Mendele website (https://sites.google.com/site/mendeledervaylik/library). I was so impressed that I decided to translate them, just for fun and to practice my Yiddish. Later on, I found that the English translations had already been published in Howe and Greenberg’s A Treasury of Yiddish Stories, but by then I was hooked on both Rosenfeld and Yiddish translation.

So what exactly impressed me about Rosenfeld’s stories? I’d have to say, first and foremost, it’s his psychological insights. He’s not entirely alone in that: other authors of his time were psychologically astute and wrote compelling character studies. But Rosenfeld went a bit beyond, in that his stories are like Greek tragedies. His protagonists fail in their quests for love, belonging, and security, not because of external forces, but because of internal, self-defeating habits of thought that they may not be consciously aware of. Rosenfeld isn’t the only author to use this psychological approach in fiction, but he does so consistently and, to my mind, very believably.

SUP: How are Jonah Rosenfeld’s stories different from the idealized portraits of shtetl life written by Rosenfeld’s peers at the time?

RM: First, I’d like to say that not all of Rosenfeld’s peers were writing idealized portraits of shtetl life, although some were – perhaps as a nostalgic response to emigration to the US and other countries. Naturally people missed the communities and traditions they’d left behind and wrote sentimental stories, plays, and songs about them. Also, there is a tendency among those of us who never experienced pre-Holocaust Jewish culture to sentimentalize our ancestors’ way of life – “Fiddler on the Roof” is an obvious example. However, as more and more Yiddish literature is being translated and published nowadays, we can see that many authors, like Rosenfeld, present a more nuanced and challenging perspective on prewar Jewish life.

Having said that, I do think most of Rosenfeld’s stories are different from many of those his contemporaries wrote.

First, Rosenfeld’s stories typically focus on an individual who does not have the support of family, friends, community, or traditions and is often at odds – even in open conflict – with them. His characters are typically those who are socially marginalized, such as women, children, older people, immigrants, and others who are alienated and impoverished: financially, socially, and spiritually. They are solitary individuals who struggle, almost always unsuccessfully, to build bridges between themselves and the hostile, rapidly changing world around them.

In our time of social and physical isolation, fragmenting communities, and rapid social change, Rosenfeld’s stories have a particular resonance.

SUP: Jonah Rosenfeld was a major literary figure of his time. Why do you feel his stories about loneliness, social anxiety, and longing for meaningful relationships are as relevant today as they were when he wrote them in the 1920’s?

RM: What’s not relevant about loneliness, social anxiety and the longing for satisfying relationships – not to mention male-female relationships, generational conflict, immigration, culture clash, child and spousal abuse, abortion, suicide, and prejudice? These are obviously deeply meaningful human issues that, 100 years after Rosenfeld’s stories were written, we grapple with today. We are struggling with the concept of impending, frightening change even more than ever.

Rosenfeld’s psychological insights are also relevant today. The author was an intuitive psychologist, and many of his stories stand up well to current theories of human thought and behavior. For example, the protagonist of “The Rivals” is a classic malignant narcissist. It’s interesting to note that the story was first published in 1909, several years before Otto Rank’s and Sigmund Freud’s theories of narcissism came out. So despite his characters living in a social, historical, and political milieu that’s different from ours in many regards, their actions and reactions are deeply human and understandable to the modern reader.

SUP: You selected 19 stories for this book. What make these stories important?

RM: We’ve already talked about Rosenfeld’s themes of social alienation and his psychological insights. To take a somewhat different perspective on the importance of his work, I want to focus on readers.

I’ve taught both business and academic writing, and I know one of the most important things for a writer to consider is the reader. Even before I started putting together the collection, I wondered who its readers would be. Because I’ve been teaching undergraduate literature courses for many years, I decided I wanted the stories to be read by students, and not necessarily just Jewish students. So I chose stories that I thought would work well in the classroom: stories that would be of interest to students and instructors and that would be teachable in terms of their themes, characters, symbols, imagery, and so on.

Eventually, after gathering my courage a bit, I taught a number of the stories in the collection to my students at Langara College. None, or almost none, are Jewish. Many are immigrants or international students from South and Central America, India, China, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere. A number of students are themselves struggling with the issues that Rosenfeld’s stories address.

Students LOVED the stories! They commented on Rosenfeld’s understanding of women, marveled that these 100-year-old stories were so relevant to their lives, wanted to know more about Yiddish and Jewish culture, and wondered where they could find similar stories. Some students confided to me that Rosenfeld’s stories had helped them understand their own family dynamics better. Occasionally I found it difficult to cover the points I wanted to make in class because the students were so eager to discuss the stories that I couldn’t get a word in edgewise!

SUP: What makes this book a must-read for fans of Yiddish literature and Jewish culture?

RM: Let me sum up: First, Jonah Rosenfeld’s stories address many concerns that are deeply relevant to us today. Second, his psychological insight into his characters make the stories quirky, interesting, and relatable. Third, for those teachers among us, the stories are fun to teach, meaningful to students, and lend themselves to assignments that are hard to plagiarize.

SUP: Of course, in this collection we’re not reading Jonah Rosenfeld’s original words, which were Yiddish, but your translation of them. What was the most challenging thing about translating these stories?

RM: All translators struggle with various elements of language: vocabulary, register (formal versus informal), idioms, word order, and so on. When translating Rosenfeld, I was also dealing with ideas relating to Jewish culture and religion. “Shabbes,” for instance, obviously means Saturday, but the connotations run much deeper in a Jewish religious or cultural context. So how to translate the word? That’s just one small example. Another problem I ran into repeatedly has do with simple matters of daily life that were very different 100 years ago than today. For example, in one story, a character drives his wife to the doctor’s office “in his own car.” Most people didn’t have their own cars at that time, so “own” implies a certain degree of wealth and social status. But times have changed, and now the phrase looks a bit strange.

And then there’s that paragraph in “Francisco” in which the main character does a quick repair job on a samovar. Not being intimately familiar with samovars (let alone broken ones), I had to figure out what was going on in that passage, which required hours of research – thank you, Google! – before I could even begin to translate it.

SUP: If you could turn back time and sit down for a cup of coffee with Jonah Rosenfeld, what’s the first question you would ask him?

RM: Mr. Rosenfeld, how do you fix a samovar?

No seriously … I think it’d be, “What were your literary influences?” What fiction did Rosenfeld read? As an author who wrote about the subconscious, was he familiar with Freud? To what degree did his own life and experiences influence his dark view of human nature?

I should add here that, at least according to what I’ve read, Rosenfeld’s contemporaries did not see him as a dark, gloomy person. They described him as melancholy at times (who isn’t?), but also as humorous, friendly, and good-natured.

SUP: Which is your favorite story in the book and why?

RM: I like all the stories, but one that stands out for me is “Here’s the Story.” Here the author takes a different approach. The main character is a stand-in for Rosenfeld himself – a writer of Yiddish stories on a reading tour in some non-specified eastern European shtetl. There he’s introduced to a “shegetz,” a gentile who is fluent in Yiddish, loves Yiddish literature, and becomes Rosenfeld’s rival in a love interest. In this rare departure, a comedy (though not without its darker elements), the author explores Jewish-Christian relationships, class relationships within the shtetl community, and attitudes towards Yiddish language and literature. It’s a peek into shtetl life – a prewar Jewish society many of us never imagined.

SUP: Your dedication to the preservation of Jewish history is evident with the publication of this book. You’ve also created the website https://shtetlshkud.com/ dedicated to a once-vibrant and thriving Jewish community in Lithuania . Can you tell us more about this site?

RM: Feel free to click on the link and take a quick tour! But here’s some background. My father, a Holocaust survivor, was born and raised in Skuodas, Lithuania. He rarely talked about his youth or family there. Over 25 years after his death, my brother and I first visited Skuodas, after which I’ve been back several times and have made – and continue to make – friends and connections among the citizens. Many of have them shared their stories of the prewar Jewish community. Assembling all of the information I could possibly find, I attempted, on this website, to “recreate” the prewar Jewish community as a memorial and also as a place for other Skuodas descendants to find out about their ancestral town and families.

September 30, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight | Leave a comment

Religion and Politics an interview with ‘Tabernacle of Hate’ author Kerry Noble

With all the talk in the media about domestic terrorism, now seems to be the right time for an interview of Kerry Noble, the author of ‘Tabernacle of Hate Seduction into Right-Wing Extremism, Second Edition’ an unprecedented first-person account of how a small spiritual community moved from mainstream religious beliefs to increasingly extreme positions, eventually transforming into a domestic terrorist organization.

SUP: Kerry tell us a little bit about your background and what made you write ‘Tabernacle of Hate’

Kerry Noble: My wife, Kay, and I moved to a small, rural Christian community in 1977. At that time, it was a peaceful, non-racist, non-violent group, where some Christian families wanted to raise their families in the country, away from the chaos of the big cities, work together, live on the same property together and fellowship together. Everything was great for the first year until we started meeting the wrong people at the wrong time. Although we were an apocalyptic church, preparing for the last days for Christ’s return, we weren’t setting any dates for whatever scenario might occur.

Then in 1978, we came upon a man talking about groups preparing, like us, storing food, clothing and supplies to house people when the chaos occurred. He asked how would we protect ourselves from all the looters coming from the big cities? This really had not occurred to us. He said we needed to protect ourselves with guns. This made sense, so over the next 18 months we spent $52,000 on guns, ammo, and military gear. We began to train with the weapons and eventually our group was large enough that we started forming paramilitary squads and we learned to be Survivalists. We eventually set up a training school and built a 4-block mock town to train in, called Silhouette City. We became known as the #1 civilian SWAT team in America.

In late 1979 we were introduced to a theology known as Christian Identity. They taught that the Jews were a counterfeit race, descended from Eve having sex with the devil in the Garden of Eden, and that the white race was the true Israel of the Bible and that the non-white races were inferior races, created before Adam. This was pretty foreign to us but by the spring of 1980 we had adapted it into our own theology. Now we were racists.

In 1981 we adapted the name CSA – the Covenant, Sword & Arm of the Lord – the now-public name for our paramilitary unit, rather than using our church name (Zarephath-Horeb Community Church) during the publicity we received over the next 4 years. Unfortunately, our group became so radicalized we began doing illegal activities off our property – we plotted the original bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1983 and the assassination of a federal judge, federal prosecuting attorney, and an FBI agent in that same year. The plans were unsuccessful in their planning, fortunately. By then we had automatic weapons, silencers, C-4 explosives, a LAW rocket, and hand grenades. In the summer of 1984, I went to Kansas City to murder gays at a park and to blow up an adult video store. Those were unsuccessful also. But the next day I took a bomb into a gay church with the intention of blowing it up during the Sunday service. Because of the actions of the gay community at that church, I decided not to set the bomb and walked out. The gay community unknowingly saved my life and began my own transition away from hate.

In the fall of 1984 members of the Order, another extremist group that had robbed armored vehicles, counterfeited money and had assassinated Jewish talk-show host, Alan Berg, began to get arrested. Some of those members were former members of CSA who eventually turned state’s evidence against us, testifying against us in 1985.

Because of this and our own illegal activities, the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team, with 300 federal, state and local officers, raised our group on April 19,1985 and we had a 4-day armed standoff, until the leader of our group agreed to surrender. I had been the negotiator between our group and the FBI – I had also been the PR guy for our group and the main Bible study teacher. By the end of May 1985 all the other leaders of the group, including myself, were arrested. I pled down to a conspiracy charge, received a 5-year sentence, and served 26 months in jail and prison. I finished my time in 1990.

I wrote “Tabernacle of Hate” originally as therapy and healing for myself, plus to get the record straight about what happened during those days. Several books had been written that included us, most of which had wrong information. I also wanted people to understand the theology and extremist mindset behind right-wing, hate mentality, with all its conspiracy theories, and to help others understand how the leaders of this movement manipulated followers with fear and hate, behind the cloak of patriotism and Christianity.

SUP: The Covenant, Sword, and Arm of the Lord (CSA) was an extremist paramilitary group in the 1970s and 80’s. Where are they now, and what can religious organizations today learn from their experience?

Kerry Noble: CSA disbanded in 1986 after the siege and almost all the men were arrested. The women and children scattered, mostly returning to the original areas they had come from. As the men were released, they joined their families. Almost all the families turned their backs on right-wing movement and its’ racism. A few still hold the previous views.

Religious organizations today need to understand that scripture says that judgement begins in the house of God – with the church. Judgement is not what Jesus came to do. Most churches preach judgment and “sin” of others, while ignoring the sins of their own congregation or of other Christian organizations. It’s the same old “us vs. them” mentality of covering up one’s own failures while pointing the fingers to others they disagree with.

SUP: As the group’s spiritual leader you helped negotiate for a peaceful surrender in an intense stand-off with federal agents, this negotiation is considered by federal agencies to be one of their greatest successes when faced with what we today would call domestic terrorism. What do you remember most about this situation and what contributed to your success?

Kerry Noble: I remember it all as if it were yesterday. By the second day I thought we were going to die in a shootout with the government. But by the grace of God, the leader of the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team had been told to negotiate as well, which he had never done before. He and I hit it off immediately and I felt like I could trust him. Ten years later we met again and eventually became friends. It’s something I am very proud of and thankful for. After the leader of our group surrendered, the ATF Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives spent 4 days searching the property for evidence. They took care of our animals and pretty much cleaned up after themselves by the time they left. I was very impressed. What impressed me most was that the federal government, whom I had learned to distrust, kept their word, whereas the right-wing leaders, including our own, had consistently lied and had revealed their true motives – fame, some wealth, and a lot of polygamy.

SUP: ‘Tabernacle of Hate’ includes two pamphlets: “Witchcraft and the Illuminati” and “Prepare War” that you wrote for the CSA that are otherwise unavailable. Can you tell us about them and why you included them in the book?

Kerry Noble: I wrote 5 or 6 booklets but these two were the most popular, along with our training manual. Originally they were propaganda books, espousing our doctrine of Christian Identity and the source behind the troubles in America and the world, and our scripture basis for making war during the Tribulation period of the last days, since we did not believe in the Rapture before the Coming of Christ, where Christians would be taken to heaven before the world was judged.

I wanted them in the 2nd edition to help people understand the depth of deception that surrounds and penetrates those who are involved in right-wing extremism, from evangelical church to the KKK and to the Lone Wolf ideology of war. It all has a common thread of fear and hate and division, which, unfortunately, still exists today and is tearing this country apart.

SUP: The book has been described as the only first-hand account available to scholars from the leader of a right-wing cult that describes how a cult develops from a mainstream community, and how people can emerge from cult beliefs. What are the most important takeaways from this book?

Kerry Noble: Wow, there are so many. I am honored that this book stands above all others written about the extremist movement and mentality and am very thankful for how it has been received, and for Syracuse University Press’ courage to republish it. Some of the takeaways are:

- Anyone can be deceived to the point of becoming the antithesis of the original individual. One does not have to be crazy or have come from a bad environment to end up an extremist. One of the main purposes of my book was to help people see and understand how one can go from point A to point Z almost logically.

- The rhetoric and mentality of “us vs them” is not exclusive to right-wingers but to left-wing extremists also. The mentality of separation and division never solves problems – it is only the consensus of “WE” (Without Exclusion) that can solve the difficult world we live in.

- There is always Hope. We were so blessed with being able to have come out of CSA as well as we did. Almost all of us have gone on with life. Becoming friends with the FBI leader was a huge irony, one of many. Had it not been for him and the grace of God, I’d have never seen my children grown up and I might never have heard the word “Papa” from my grandchildren. I am a blessed man.

My later book is called, “Tabernacle of Hope: Bridging Your Darkened Past Toward a Brighter Future.” It’s about the lessons I learn in my journey and that hope is there. It is my prayer that America bridges its now-darkened present toward what can be a much brighter future for us all. Thank you.

For more information on ‘Tabernacle of Hate’ click on the book below.

September 23, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight, Uncategorized | Leave a comment

International Literacy Day Featured Interview with “Off the Beaten Path” author Ruth Colvin

We couldn’t celebrate International Literacy Day without interviewing author Ruth Colvin, a woman who has dedicated her life to literacy, founded Literacy Volunteers of America, and written the fascinating memoir “Off the Beaten Path” about her experiences providing literacy training around the globe.

SUP: What inspired you to spend a lifetime promoting literacy around the world, what was it that drew you to this career?

Ruth Colvin: I can’t believe a life without reading, so in 1960 when I saw in our local paper the 1960 US Census figures stating that there were 11,055 functional illiterates in MY city of Syracuse, NY, I wondered who they were, why couldn’t they read, and what was being done about it. My research showed that nothing was being done. So, I had a coffee at my home, inviting members of the Board of Education, Presidents of non-profits, all men except one woman. They were as shocked as I was, but no one offered to do anything except the one woman from Church Women United, representing the women of 90 churches. She asked me to speak to her group, and they voted unanimously to start a literacy project but only if I would take charge. That was the start of Literacy Volunteers of America (LVA). But it was when I asked Syracuse University’s professional reading experts to help me that I learned the basics of teaching literacy, never dreaming that it was a national problem and that LVA would grow around the entire country.

SUP: Did you realize at the time how far around the world your passion would take you?

Ruth Colvin: I never dreamed that it was a world problem and that I would be invited to give literacy training in 26 developing countries.

SUP: You’ve met people from all walks of life—a holy man in India, a banned leader and a revolutionary in the apartheid system of South Africa, lepers in India and Madagascar, and survivors of Pol Pot’s Cambodia to mention a few. Of all the people you’ve met along the way, who had the greatest impact on you and why?

Ruth Colvin: Each developing country was a learning experience for me, but it was the people I met who touched my life – the poorest people living in hutments, in poverty, having had no education, who were surviving and always helping each other, and the leaders who were amazing, most working hard to solve the problems of their country.

SUP: Author David Baldacci has said “Ruth Colvin exemplifies the power of one individual changing the world for the better,” and former first lady Barbara Bush has described you as “a living testament to the literacy cause.” Of all the things that you have done, what would you say makes you the proudest?

Ruth Colvin: I think I’m most proud of those that helped me along the way, for it has been lifelong learning for me. And for those that listened and learned, and it became their passion as well as mine, for after I left, they had to carry on. I’m so proud of the students, the tutors, the board members and staff of affiliates around the country, and for them to be creative, sharing their successes with ProLiteracy to share around the world.

SUP: If you could throw a dinner party and invite one person you haven’t already met from anywhere in the world to sit and discuss literacy, who would it be?

Ruth Colvin: Looking back, I think it would be someone who I had taught to read and write, who because of that had a most successful life, helping others.

SUP: Your passion for literacy has earned you nine honorary doctorates, the highest award for volunteerism in the United States, the President’s Volunteer Action Award, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, your passion inspires the world. Who inspired you along the way?

Ruth Colvin: People have heard of my successes, but few have heard of my rejections, for I was living in a “man’s world,” where women weren’t allowed or expected to create anything new, to lead in any way, no matter how much it was needed. It was Bob, my husband, the love of my life, who saw and understood my passion, and supported me all the way, keeping my passion and inspiration alive.

SUP: In your personal opinion, what impact do you think the current pandemic will have on literacy?

Ruth Colvin: The current pandemic has an impact on everyone and everything, but because I always have a positive attitude, I look to see how Literacy Volunteers of America (now ProLiteracy) can be helpful. It’s impossible for most one-on-one meetings to continue, but we must look to the future and encourage tutors and learners not lose contact, so we’re suggesting they keep in contact by phone, by sharing the same books and sharing lesson plans by mail, so some lessons can continue. Many of the immigrants who have very limited English as a second language, don’t understand the pandemic necessities. It’s individual tutors who have been working with them that they trust. Those tutors then, by Skype, by Zoom, by iPhone, by phone, can explain, in the simplest language, why masks sanitation and social distancing are so important.

SUP: “Off the Beaten Path: Stories of People Around the World” takes readers along your journey around the world promoting literacy. What do you think readers will enjoy the most about your book and your adventures in teaching?

Ruth Colvin: Because travel is so limited now, I think readers will enjoy sharing my travels to places where it’s impossible for them to be. Again I say, it’s lifelong learning, and readers can learn about geography, about how people live around the world, those in poverty and those in leadership and wealth, and how we can help each other.

September 8, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight | Leave a comment

Editor Q&A: Guilt Rules All

Fans of Irish crime fiction are no strangers to anticipation. From the classic police procedural to the emerging domestic noir, this genre and its nail-biting stories have exploded across the global literary sphere. And that popularity is in no small part due to the curiosity and excitement that readers feel as they consume this popular fiction. We at Syracuse University Press are feeling the same way about the publication of Guilt Rules All, edited by Elizabeth Mannion and Brian Cliff. Guilt Rules All is an essay collection that explores the roots and also the fluidity of this developing genre. Both scholars and enthusiasts of Irish crime fiction have come together to discuss topics spanning from globalization, to women and violence, and even to Irish historical topics like the Troubles. We asked Cliff and Mannion to tell us a little more about how the project was started, why the collaborative format, and where their love for Irish crime fiction began.

Guilt Rules All hopes to find an audience in both the academic sphere of Irish Studies and with the general readership of Irish crime fiction. How was it trying to balance this diverse readership spanning from scholars to aficionados?

For the most part, it was exciting and a bit liberating. We’ve worked hard to make sure the collection offers insights to Irish Studies scholars new to crime fiction criticism, while doing just as much to welcome experienced crime fiction readers and scholars who may be newer to Irish materials.

Of the five sections of Guilt Rules All, the final discusses the very recently emerged subgenre of domestic noir. This subgenre, and the entirety of Irish crime fiction, is deeply influenced by female writers. How is the discussion of women authors and their work addressed in this collection?

A central goal as we developed this collection was to make the contents reflect the full scope of subgenres and the ways women are writing across all of them, from police procedurals to psychological thrillers. So many women are producing some of the richest, most exciting Irish fiction of any genre, and accounts of Irish crime fiction need to address that in detail. Not enough critical work has yet been done on writers beyond Tana French and Benjamin Black, but any dive into Irish crime writing will reveal that writers like Julie Parsons and Arlene Hunt were there from the earliest stages of the genre’s recent growth.

What unique perspectives do nonacademic writers bring to the discussion of Irish crime fiction, that Guilt Rules All would suffer without?

Mannion: Gerard Brennan has a PhD from Queen’s Belfast, so he has one foot in that academic world, but his other is firmly set in the creative realm. Like Declan Burke, who has perhaps done more than anyone to spread the word about Irish crime fiction’s strengths, Brennan is a seasoned crime writer. Both Declan and Gerard were important to this collection because they were able to discuss their subjects – Steve Cavanagh for Gerard, and Alex Barclay for Declan – from the perspective of practicing novelists. Joe Long’s perspective is that of a hard-core fan. He’s one of the undersung heroes of Irish crime writing in America, a real advocate for these writers. Together, these three contributors reflect some of the different perspectives from which people have done so much to support the genre’s growth in recent decades.

In editing Guilt Rules All, what new or different conclusions did you come to about the Irish crime fiction genre?

Both of us have worked extensively on the genre, Beth with her 2016 edited collection The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel and Brian with his 2018 monograph Irish Crime Fiction. The experience of editing and contributing to Guilt Rules All was another reminder of just how diverse and energetic the genre is, and an exciting chance to see what insights our colleagues have been able to glean from their array of authors. The main conclusion we’ve reached is that Irish crime fiction – in general, and in the particulars given here – is marked by a defining fluidity and a generosity in fusing subgenres. These traits show how both crime fiction and Irish literature are more capacious than they may sometimes seem. It’s our hope that, by tracing these traits, these essays will contribute to a foundation on which to build further accounts of the genre’s role in Irish culture. It’s also become crystal clear to us that there are some amazing scholars out there who want to track those directions.

What was the impetus for Guilt Rules All? Why this book, and why a collaborative project?

We had worked well together on The Contemporary Irish Detective Novel, to which Brian contributed a chapter on John Connolly’s work, and we had a number of discussions about what – beyond our own previous publications – could be done to broaden the discussion’s scope, and to reflect the range of authors who’ve made a place for themselves in that discussion. We also saw that the field was expanding faster than most readers can keep up. It was important to us that an attempt be made to keep pace and—before too much more time passed—capture the impact of some writers who were there before the field gained international attention.

Love of Irish crime fiction shines through every chapter of Guilt Rules All. As this passion propels the collection, can you recall your introduction to the genre? What was the first book or series that lit the spark?

Mannion: My sparks were Declan Hughes and Jane Casey. I was familiar with Declan’s plays, and when I heard he wrote crime fiction, I jumped in. I think Brian is the person who introduced me to Jane’s Maeve Kerrigan series. I was hooked with the first book (The Burning).

Cliff: My reading of crime fiction in general was set off decades ago with the Irish poet Paul Muldoon’s “Immram,” which fuses to delirious effect the Southern California of Chandler and Macdonald with medieval Irish vision quests. My specific love for Irish crime fiction, though, began with John Connolly’s Charlie Parker series, Tana French’s Faithful Place, and Jane Casey’s Maeve Kerrigan series.

In your opinion, why is Irish crime fiction such a booming genre in today’s global literary field?

As we explore in our introduction, the genre’s growth really kicks in at a point where many of the parameters of Irish fiction in general could seem at times to have been pretty thoroughly delineated, but Irish crime fiction – like other forms of popular fiction in Ireland – has offered a wealth of new angles, perspectives, and approaches, to which scholars are increasingly attending. At the same time, for genre readers outside of Ireland, Irish crime fiction offers characters and contexts that are accessible to a wide range of readers in and beyond the Irish diaspora, while still maintaining a strong sense of specificity, a combination that seems to give readers an easy path into a complex world.

March 20, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight, New Books, Recently Published | Tags: editors, Guilt Rules All, Interview, Q&A, spotlight | Leave a comment

Author Spotlight

A Conversation with Rick Burton & Scott Pitoniak authors of “Forever Orange: The Story of Syracuse University”

SU Press: March 24th marks the sesquicentennial of Syracuse University. What in SU’s 150-year history do you think readers will find most fascinating and why?

Scott: Since its inception in 1870, SU was ahead of the curve, opening its doors to females, students of color and international students long before other institutions became inclusive. When I think of SU, I don’t think just of Jim Brown or Dick Clark or Bob Costas, but also of pioneering alumni such as Ruth Colvin, who founded literacy volunteers, and Belva Lockwood, the first woman to argue cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and run a full campaign for president. I think of Dr. Robert Jarvik, the inventor of the first artificial heart, and literary giants such as Joyce Carol Oates, Shirley Jackson and George Saunders. I think of Hollywood and Broadway heavyweights, like Vanessa Williams, Aaron Sorkin and Detective Columbo himself – Peter Falk. And I think of SU’s strong ties to NASA, especially Eileen Collins, the first female space shuttle pilot and commander. The list of extraordinary SU people in all walks of life goes on and on – so much so that Rick and I found it impossible to include everyone who deserved to be included, given the space and time constraints.

SU Press: How about faculty that left the greatest impact?

Rick: We showcased/featured approximately 20 in our “It’s Academic” chapter, but could have written about 200 – if not more.

SU Press: How has the university changed the most in its 150 years?

Rick: I’m not sure that it has. It’s bigger and more famous – a globally recognized ‘brand’ – but it still sits on its hill overlooking the Onondaga Valley and the city of Syracuse. It still attracts amazing students and faculty and it still generates world-class and world altering results. Scott and I may share a bias, a love for Syracuse, but there is no denying that the flag so many of us treasure means a great deal to a lot of us.

Scott: I agree with Rick. To paraphrase that great philosopher and wordsmith, Yogi Berra, “it’s changed, but it hasn’t.” It’s stayed true to its original mission statement espoused by founding father, Bishop Jesse Truesdale Peck. Undoubtedly inspired by the women’s suffragist movement at nearby Seneca Falls and the abolition of slavery brought about by the end of the Civil War just five years earlier, Peck called for admissions to be open to all persons, regardless of gender, skin color or religion. In his inaugural address, he said, “brains and heart shall have a fair chance.”

SU Press: What was the most rewarding part of writing this fascinating book?

Rick: I would say working with Scott and discovering the fine details on so many nuanced stories. We’ve all heard bits and pieces about someone famous or a notable event, but have rarely been able to find them in one setting with rich narrative and stunning photography.

Scott: I second Rick’s sentiments. It was wonderful working with him and getting to know him better as a person. As a former student and current journalist, I thought I knew pretty much all there was to know about my alma mater. How wrong I was! This turned into a labor of love because I’m a history buff and because I’ll always be grateful for the lasting impact Syracuse has had on me. SU truly was a place where I blossomed as a person; a place that launched this five-decade-long story-telling career of mine. To be able to do a deep-dive, and tell the story of this place that’s profoundly influenced my life, Rick’s life and the lives of millions of others was amazing.

SU Press: How did you cover 150 years of history in one book?

Rick: To quote the Beatles, we turned left at Greenland. The more appropriate answer is that we only scratched the surface. SU is historically significant in so many ways and we approached our task of wanting to make the treasured moments, the alums, faculty and events come to life. But entire books could be written about any one of the subjects we touched upon. Let’s say it this way … we tried, with a historian’s eye (think of us as a giant Cyclops) … to make the history of the last 150 years come to life through the words and the actions of the people who created that history.

SU Press: What are your personal favorite parts of the book, images, stories?

Rick: Springsteen’s Born to Run album cover; the New York Yankees logo; F. Story Musgrave fixing the Hubble Telescope; Dr. King on the Mall in Washington D.C.; the six-overtime box score from a historic basketball game Syracuse easily could’ve lost; a story about the Jabberwocky; photos of M Street, etc. The list for each of us would be endless because each story we wrote helped comprise the mosaic we were intending. And each photo or graphic colored those stones so that someone could see Orange in the spectrum of hues presented.

Scott: I think the stories that resonated most for me were the essays about 44 alumni of note in the middle of the book. F. Story Musgrave’s story, in particular, struck a chord. He is one of the most significant astronauts of all-time, a true genius who earned five graduate degrees and also became a surgeon. What makes his story all the more remarkable is that he dropped out of high school to join the Armed Forces. At the end of his service, he applied to Syracuse. Because he didn’t have a high school diploma, several members of the admissions committee wanted to reject him. But one committee member advocated on Musgrave’s behalf, saw great potential in him, so Musgrave was accepted. His story speaks to the bigger story of how Syracuse has often taken chances on “marginal” students like Musgrave with remarkable results.

I also loved researching and writing about famous visitors, everyone from Presidents of the United States to Babe Ruth. One of my favorite stories is how Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “auditioned” his I Have a Dream and I’ve Been to the Mountaintop speeches on the SU campus. Those speeches, along with Lyndon Johnson’s “Gulf of Tonkin” address during the dedication of Newhouse I, are reminders that history often happened here.

SU Press: Why should readers be interested in Forever Orange?

Rick: If they have a connection to Syracuse University, Forever Orange gives them a treasure trove of short stories, long features and images that will allow them to appreciate the breadth and diversity of our university. SU has really been an amazing place for the last 150 years and the very entities still survive in their original form from 1870. I think it’s safe to say that the mission envisioned at the beginning is one that still resonates today.Scott: Supercalifragilisticexpealidocious! That’s why they should read the book. 😉 In all seriousness, that funny-sounding, non-sensical, 14-syllable word popularized in the film Mary Poppins has Orange origins. While researching Forever Orange, I discovered the Oxford English Dictionary traces the word’s birth to a column written by SU student Helen Herman in the student newspaper in 1931. The word means “extremely good and wonderful.” We have hundreds of these “Wow! I didn’t know that!” revelations in this book, which we obviously hope readers will find extremely good and wonderful.

March 19, 2020 | Categories: Author Spotlight | Leave a comment

Author Spotlight: Charles Kastner

In honor of Black History Month, we interviewed author Charles Kastner who has written multiple books on the 1928 and 1929 ‘Bunion Derbies’. His most recent book on these transcontinental races, Race across America, focuses on the struggles of one of the few black racers participating in the derbies. Eddie ‘the Sheik’ Gardner ran through states that did everything except welcome him, yet persevered and inspired Black Americans throughout this journey.

Do you remember when you first learned about the ‘Bunion Derbies’? Did you learn about Eddie Gardner then as well, or did that come to light throughout your years of research?

My introduction to the Bunion Derbies began while my father-in-law lay dying in a hospital bed in Seattle—a sad start to a topic that would occupy my time for the next twenty-two years. He told me about a footrace he remembered from his childhood that started in Port Townsend and finished in Port Angeles, Washington, a race distance of about fifty miles. At first, his statement seemed hard to believe: I had no idea that people were competing at the ultra-marathon distances so long ago.

Several months after his death, I traveled from my home in Seattle to Port Angeles and began scrolling through rolls of microfiche at the city local library to see if I could uncover any information about the race. This was before the days of digitized newspapers. Finally, in the roll marked “June 1929,” I found articles in the Port Angeles Evening News about what was billed as the “Great Port Townsend to Port Angeles Bunion Derby.” My first reaction was “What is a Bunion Derby?” and my second was “Why would a bunch of ‘average Joes’—lumberjacks, farmers, postmen, and laborers—attempt such a thing?” Of the twenty-two men who started, only eleven finished the event, as they had little training and little understanding of what they had gotten themselves into. Most crossed the finish line with blisters the size of half dollars, shoes oozing blood, and legs so sore and cramped that one finisher had to crawl across the finish line–all this for small cash prizes that ranged from $100 for first to $10 for tenth. One article noted that local officials had dreamed up the event after the famous sports agent Charles C. Pyle held his first-of-its-kind trans-America footrace, or “Bunion Derby” as it was nicknamed by the press, in the spring of 1928. The article also mentioned that a Seattle runner, Eddie “the Sheik” Gardner, had competed in the event. That information piqued my interest.

After I returned home, I went to the main branch of the Seattle Public Library, pulled rolls of microfilm from the newspaper file and began scanning through the sports pages of the Seattle Post- Intelligencer and the Seattle Times. I quickly found article after article about the event starting in late February 1928. I then realized that Seattle’s entry, Eddie Gardner, was black. I wondered about the challenges a black runner would face running in an integrated footrace, especially when the 1928 race took the derby through Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri, where either by custom or law, blacks and whites were not supposed to compete against each other in sporting events. I also learned that Gardner earned his nickname “the Sheik” from his trademark outfit he wore when he competed in local footraces. Wearing a white towel tied around his head, with a white sleeveless shirt and white shorts, he reminded his Seattle fans of Rudolph Valentino, a 1920’s heartthrob who starred in the silent films “The Sheik” in 1921 and “The Son of the Sheik” in 1926. For the rest of his life, local sports writers referred to him as Eddie “the Sheik” Gardner.

How did you decide to specifically highlight Gardner out of the five African American runners who participated in this race?

Eddie Gardner was the only black runner who could challenge his white competitors for the $25,000 first place prize money in the 1928 derby. The other African American bunioneers were out of contention for any prize money–the top ten finishers with the lowest cumulative times won cash that ranged from $25,000 for first to $1,000 for tenth–and hoped only to complete the 3,400-mile course. Eddie Gardner’s elite status made him the focus of the taunts and death threats that white fans felt free to hurl at him as the bunioneers passed through Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Gardner had a brutal passage through these three Jim Crow states. In Texas, he held back from challenging the lead runners out of fear of losing his life. When the race entered western Oklahoma, a white farmer rode behind Gardner with a gun trained on his back, daring him to pass a white man. At that point Eddie was falling out of contest for the prize money, and he had to decide if he wanted to risk his life and resume challenging the lead runners. His courageous decision to do so became a source of pride for the African American communities he passed through. The black press picked up his story, and he became a nation-wide hero to black America.

Is there any specific piece of Gardner’s story that has really stuck with you throughout your years of researching? Or a favorite part of the book itself?

Here’s the one that stands out for me. On the 24th day of the second bunion derby in 1929, Eddie was in third place after covering 1,040 miles since leaving New York City on March 31st. The next day, the derby would cross the Mississippi River into Missouri where Jim Crow segregation was the law of the land. He had been here before in 1928 and he knew what awaited him.

Despite danger, he wanted to make a statement: He ran at a sub-three-hour marathon pace on the short, 22-mile course that passed through St. Louis on the way to the finish at Maplewood, Missouri. And he had added something new to his race outfit. Eddie wore his trademark “Sheik” outfit with a white towel tied around his head, and a sleeveless white shirt, with his number 165 pinned on the shirtfront. A few inches below the number, he had sewn an American flag. It was about six inches wide and was put there for all to see. Poignantly, without words, Gardner announced his return to the Jim Crow South. Death could await him at any crossroad or from any passing car, but he kept going, unbowed by fear. Whites might kill him, beat him, or threaten him, but they could not change the fact that on this day he was running as the leader of the greatest footrace of his age and giving hope to millions of his fellow African Americans who saw him race or who read about his exploits in the black press. In the birth year of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Eddie crossed the Mississippi River with an American flag on his chest, a man willing to die for his cause.

How did you conduct your research in order to provide such a thorough account of Gardner’s experiences without being able to communicate directly with him? Are there any specific methods you use to conduct this type of research?

Reconstructing the life of someone long dead is a challenge. It’s a bit like putting a jigsaw puzzle together; each piece of information adds something to the emerging picture. Census data and death certificates helped a lot. Another important source was Eddie’s federal personnel file. In the 1950’s he worked for the U.S. Navy, refitting ships at the Bremerton Naval Shipyard near Seattle. Gardner needed a security clearance to work there. To get one, he had to fill out a lengthy background questionnaire, which was verified by Federal investigators prior to his employment. That document fleshed out a lot of his past life. Another source was Gardner’s transcripts and yearbooks from Tuskegee Institute where he attended from 1914-1918. I spent a week at what is now Tuskegee University combing through its archives. These sources combined with hundreds of newspaper articles written about the derbies, and four personal narratives, helped me come up with a detailed picture of Mr. Gardner’s life.

I started with the two bunion derbies, and both were relatively easy to follow. The 1928 edition started in Los Angeles on March 4, 1928, and finished in Madison Square Garden on May 26, 1928, after 84 days and 3,400 miles of daily ultra-marathon racing. Each day’s race or “stage run” as it was known in the vernacular of the derby stopped at a given city or town for the night. The 1929 race reversed course.