This month scholars will participate in the 75th Annual Iroquois Research Conference. In celebration of this conference, Syracuse University Press is featuring an interview with Laurence M. Hauptman.

Laurence Hauptman is a SUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History who first attended and presented at the Iroquois Research Conference in 1974. Hauptman is the author of eight books published by Syracuse University Press including Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations Since 1800 that focuses on the lives and contributions of numerous women and men who shaped Haudenosaunee history.

SUP: Professor Hauptman– You have written numerous articles as well as 8 books on the Haudenosaunee/ Iroquois published by Syracuse University Press. Yet, you yourself are not a member of the Six Nations. What drew you to your lifetime commitment to write their history and what why did you approach the subject in the way you did?

LH: Fifty years ago, after reading Anthony F. C. Wallace’s The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca while in graduate school, I made it my point to familiarize myself with the literature on the Haudenosaunee, I noticed that most of the scholarship was written by anthropologists and that there was a gap in the historical literature after the death of Handsome Lake in 1815. Encouraged by a friends, anthropologist Jack Campisi, and historian William T. Hagan, I was determined to fill in that gap by writing 19th and 20th century Haudenosaunee history.

My career as a historian also grew out of a boyhood interest in the American Civil War. I was a junior in high school during the centennial of the Civil War in 1961. From this research, I learned an important lesson, namely that military historians visit the National Archives, but also go to visit and walk the ground of Civil War sites to gain a firsthand understanding of the topography of the battlefield. Combining archival research with on-site visits and interviews in Native communities grew out of this thinking. In the process of doing fieldwork, I was to meet some of the most amazing and heroic Haudenosaunee people from Hogansburg to Green Bay and learn valuable lessons, especially from Gordy McLester, my dear friend and co-author/ co-editor on five books,. who died from Covid-19 in May..

My graduate-school training at New York University led me first to American diplomatic history and then to coursework in anthropology. After reading the wonderful writings of historian Akira Iriye, I understood how important it is to look at competing sides in international relations and what he meant by a “culture and power” approach, namely how nations see their interests through the prism of their own cultures. Hence, I never saw doing Native American history as racial minority history with all the assumptions that that conveys, but rather in a global framework since they are transnational peoples with treaties. By studying international relations, I became more aware of the need for fieldwork to understand how people think, and that to do Iroquois history, you could not merely view things from what is in the archives in Washington. Albany, or Ottawa.

In early 1968, my mentor Bayrd Still, a fine teacher-scholar of urban America and the American West, gave me advice: “We historians here do not know about Indians.” To him, the only scholars interested in what was considered an esoteric subject at the time were anthropologists. Praising his friend, the well-known anthropologist E. Adamson Hoebel, he pointed across campus to the anthropology department. When I took my first anthropology course with the eminent anthropologist June Nash, she described her own work with the Maya in Guatemala and indicated to all five of us in her graduate seminar that contact with living people was acceptable and even encouraged by the discipline of anthropology. I had not heard that point made in any of my history classes before. A light bulb appeared in my head — the exciting thought of schmoozing with live human beings! [My father was a great “schmoozer” who could make conversation with anyone, especially about baseball; he apparently gave me this ”gift.”]

My first venture into “Indian history” was my masters-level essay on the (Dawes) General Allotment Act and post-Civil War reform, completed in 1968. In 1971, in one of the ironies of my life, I was hired at SUNY New Paltz, just 5 miles from where these reformers had met at Lake Mohonk to discuss the merits of the Dawes General Allotment Act from the early 1880s until 1929.

SUP: Which of the numerous women and men you treated in Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations since 1800 made the biggest impression on you and changed your thinking?

LH: Ernest Benedict (Mohawk). I had the privilege of knowing Chief Benedict for a quarter of a century thanks to his niece, my friend Kay Olan. He represented the very best in the Haudenosaunee world, a true intellectual and one totally committed to the ideals set forth in the Great Law of Peace. Sometimes historians are too cynical and miss the point that sheer idealism can be a motivating factor in human behavior. Chief Benedict cared deeply about his people and fought from the age of fifteen for Haudenosaunee border crossing rights set under the Jay Treaty of 1794. He viewed Native Peoples in an international context whose existence was being threatened by the ever-increasing pressures of “development” worldwide, leading him to found the influential Akwesasne Notes on his kitchen table in the late 1960s.

SUP: If you were able to magically go back in time and sit down with an Haudenosaunee leader from one of your books, which one would it be and why?

LH: Chief Daniel Bread (Oneida). I wrote about Chief Bread in a chapter in Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership published by Syracuse University Press and a in a full scale biography co-written by my dear friend, the late Gordy McLester, published by the University of Oklahoma University Press. I was fascinated by Bread’s skills as a politician. He managed to hold onto power from the 1820s to the 1870s. His skill led the Oneidas to plant permanent roots in Wisconsin. He carefully brought the influential Jackson Kemper, first Frontier Bishop of the Episcopal Church and later Bishop of Wisconsin, into the Oneida orbit, using Haudenosaunee metaphors reminiscent of the Condolence Council; Kemper responded by becoming the Oneidas’ protector in Wisconsin. Bread even debated Indian removal and the fate of his Oneidas with President Andrew Jackson at the White House in 1831.

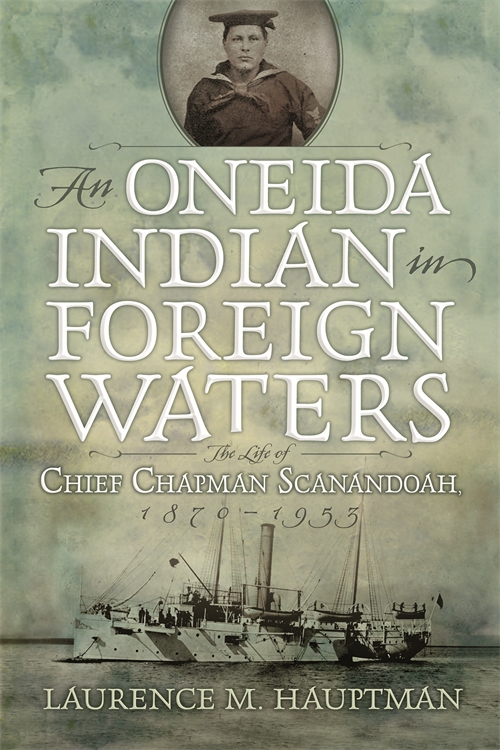

SUP: Your most recent book published with the Syracuse University Press was An Oneida Indian in Foreign Waters The Life of Chief Chapman Scanandoah, 1870-1953 (2017). Tell us about what makes Chief Chapman Scanandoah so important for you to write his biography?

LH: Chief Chapman Scanandoah. Chief Chapman Scanandoah was truly a remarkable individual. He was a well-trained mechanic, a decorated Navy veteran, a prize-winning agronomist, a historian, linguist, and philosopher, an early leader of the Oneida land claims movement, and a chief of the Oneidas. However, his fame today among his Oneida people rests with his career as an inventor. His whole life, he challenged stereotypes. On March 1, 1926, a reporter wrote about Scanandoah’s scientific accomplishments:“Chief Chapman Schanandoah [Scanandoah], sachem, Oneida Tribe of Iroquois and a resident of the Onondaga reservation at Nedrow, has won recognition from the Great White Father as an inventor in the realm of science which always has seemed the white man’s realm… He holds the confidence and the rapport of the dusky men and women in the midst of where he lives. They are glad he has won this honor in the world outside their valley and has proved the Indian of today knows tools, machines, and molecules.”[1] His life, 1870 to 1953, illustrates the Haudenosaunees’ remarkable ability to adapt to change, a major reason why all of the Six Nations in New York still maintain today a government-to-government relationship with the United States.

Scanandoah successfully managed to succeed in nearly everything he did. He was an outsider at the primarily African American Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia where he was educated in the late 1880s and early 1890s; one of the very few Native Americans in the United States Navy from 1897 to 1912 who traveled throughout the world; an Oneida with no land or political rights on the Onondaga Reservation where he resided for much of his life; a litigant in the white man’s court attempting to prevent the loss of the last remaining Oneida lands in the Empire State; a Native American inventor earning patents in the age of Thomas Edison; and one of the founders of the Indian Village at the New York State Fair.

SUP: If you were to write another book about the Haudenosaunee people in 2020, what would you focus on?

LH: I would write about the important roles attorneys play and have played in Haudenosaunee existence. Over the past half century, much of my historical research and consulting work has led me to examine historic litigation by numerous attorneys, thirty- three in all, hired to protect tribal lands and sovereignty. Although some were incompetent or unscrupulous, others I encountered in my research—e.g. James Clark Strong and George Palmer Decker – or personally worked for—e.g. George Shattuck, Arlinda Locklear (Lumbee), Jeanne Whiteing (Blackfeet)—were well versed in Haudenosaunee and American history. In order to develop strategies and represent their clients well, they like historians had to master the documents. I have found that too often historians equate the origins of every strategy affecting Native Americans in the courts entirely with chiefs, tribal chairman, and tribal councils. They all were/are very important, but many of the legal theories used in litigation were hatched by their attorneys.

The House of Representatives’ Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs’ Subcommittee on Indian Affairs’ hearing on the Seneca Nation Settlement Bill, September 13, 1990. Shown left to right are three who testified on the Seneca Nation’s behalf: Congressman Amory Houghton, Jr., the sponsor of the legislation; Dr. Laurence M. Hauptman, who served as the historical expert witness on the leases; and Dennis Lay, President of the Seneca Nation of Indians.

This entry was posted on October 14, 2020 by syrupress. It was filed under Author Spotlight .

Leave a comment